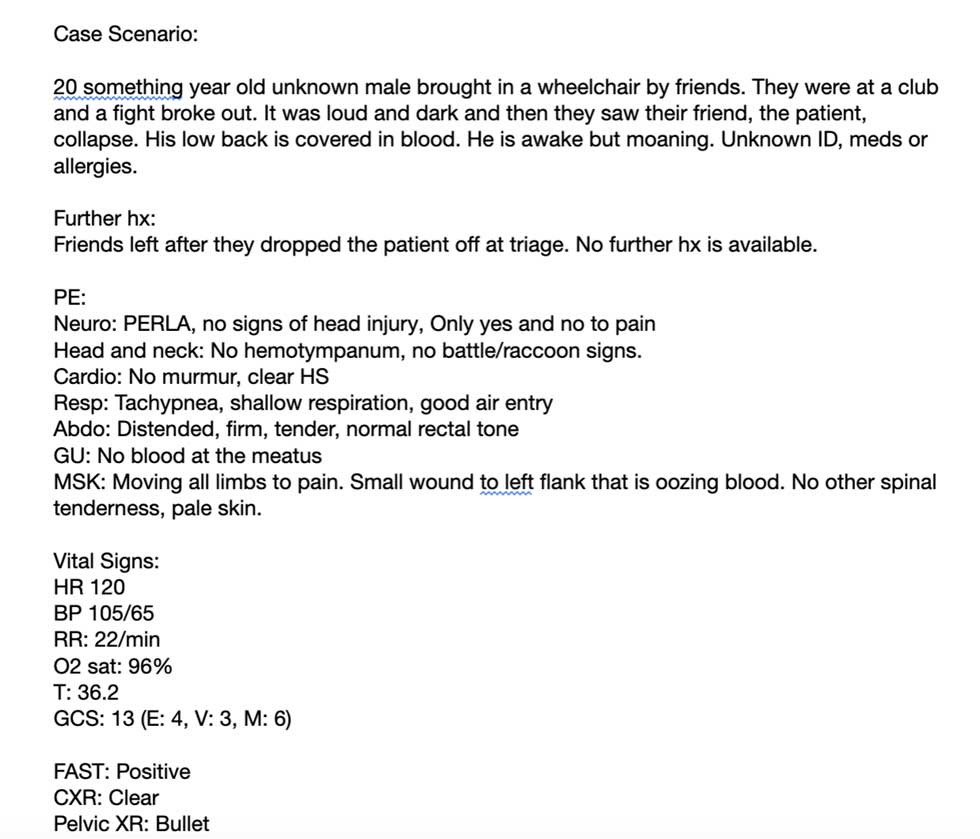

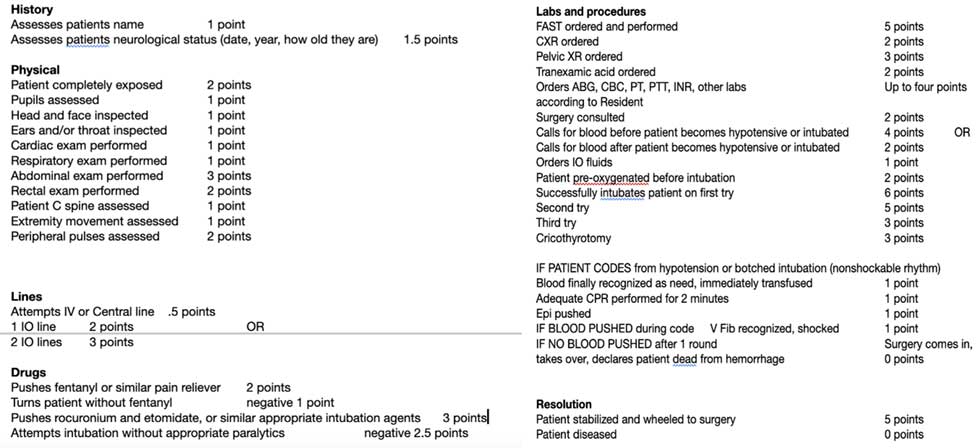

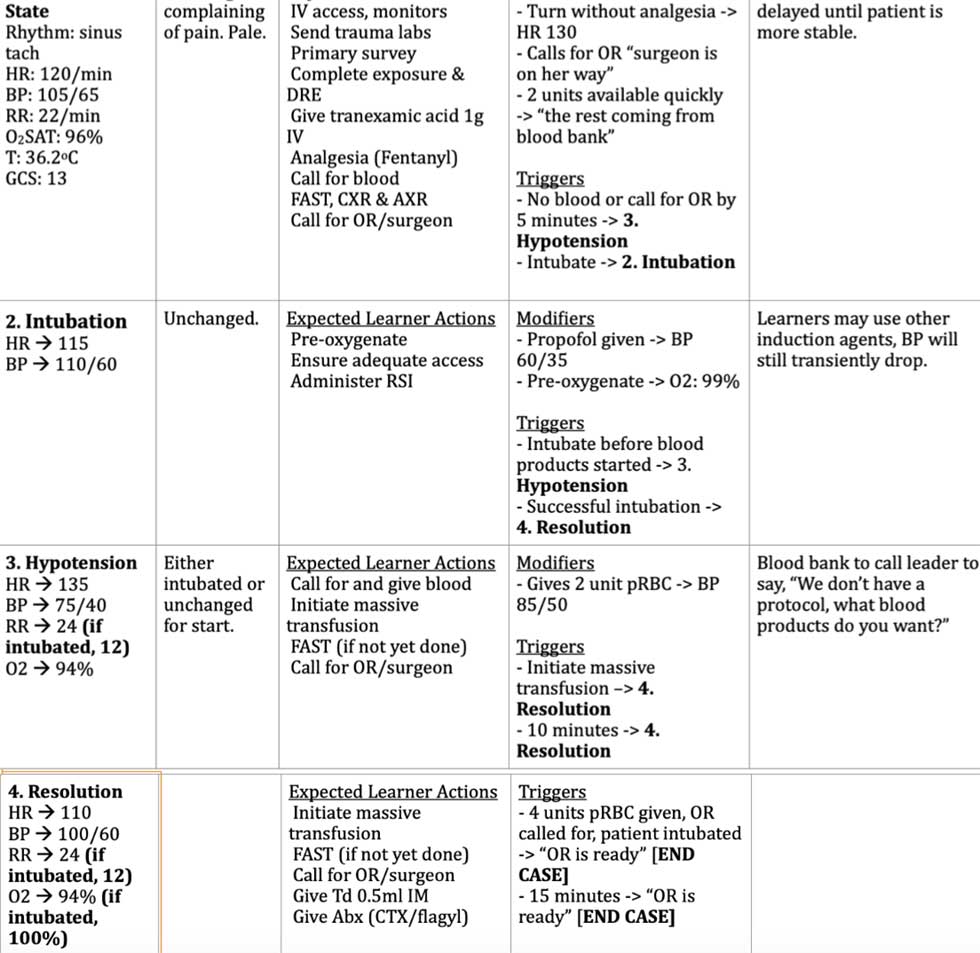

“Simulation challenges”: A novel Medical Student training toolFrank Frankovsky III, MS-2 During the first two years of medical education, much emphasis is placed on didactic course work and lectures. While this theoretical knowledge is an indispensable aspect of becoming a doctor, students often yearn to shadow, see patients, and interact with their communities in a meaningful way. However, even while volunteering or tagging alongside a resident or attending, students rarely get the opportunity to make meaningful medical decisions in the first two years of schooling. To be frank, students want to know how to practice medicine even as they are just learning what medicine is. The other knowledge gap students come across is where in the medical field they would like to commit for the entirety of their careers. While some aspects of each specialty can be revealed through mentorship and shadowing, for some high-intensity specialties such as Emergency Medicine, shadowing alone cannot reveal what it truly means to make life-or-death decisions. These gaps in the medical student experience can be addressed by student interest groups, particularly for Emergency Medicine. This second year medical student organizer, alongside an EM resident and Trauma Surgery attending, decided to organize a pilot program deemed a “simulation challenge” to better reveal to first and second year medical students what it means to be in a high-stress environment and determine whether it is something they desire for their careers. The medical student organizer reached out to a known third year Emergency Medicine resident to help draft a 15-minute clinical scenario in which up to five teams of four medical students try to save a critically-ill patient in simulation (SIM). The SIM drafted was a trauma scenario that called for Massive Transfusion Protocol (MTP) after a young man was shot in the upper left flank (figure 1)(figure 2). Sixteen medical students across four teams were given a briefing via email days before the SIM with a link to ATLS protocols listed on UpToDate for their review. The day of the event, the drafting resident recruited help from a first year Emergency Medicine intern and a trauma surgery attending, who created the debrief presentation for the medical students. Additionally, the coordinating medical student recruited a former Emergency Medicine Interest Group officer who is now a third-year student to aid in grading the SIM. The coordinating medical student aided in facilitating the event and running teams from the waiting room to the simulation within the Texas Tech University Health Science Center SimLife center. The drafting resident was running the SIM from behind a one-way mirror with the Trauma Surgery attending looking on and adjusting the response as they deemed fit (figure 3). After the SIMs were graded, the PDF of each team’s SIM was emailed to the members. The Trauma Surgery Attending led an interactive debrief on trauma responses, and the students were let out around 2 hours after the start of the event. Of the four teams of four brave medical students desperately trying to save our simulated patient, two teams successfully resuscitated the patient who was transferred to surgery while two teams lost the patient. While the participants were knowledgeable in basic medical sciences, asking pre-clinical medical students to run a trauma protocol and save an acutely dying patient required an innovative and base instinct approach not usually required of them. Even with this jump in expected knowledge to a resident-level simulation, the students enjoyed the opportunity to broaden and apply their knowledge of the human body. One student described the experience as “a ton of fun, even as stress-inducing as it was!” while another immediately asked when the next challenge would be. The residents and attending applauded the students’ efforts, with the drafting resident noting “even some of [their program’s] interns may have not saved that guy.” There were unique unforeseen challenges associated with the event that need adjustment in the future. Ensuring there is enough support staff to coordinate the event day-of and confirming the attendance of each student so that the simulations could be done as planned are important considerations for anyone planning a similar event in the future. The success of his event showed that simulation does have a place within the first few years of medical education. The student participants loved the rush of trying to bring even a model back from the brink of demise. Interdepartmental cooperation between medical students, surgery, and emergency medicine was on full display throughout the SIM, reflecting the teamwork that will be essential to the medical students’ future practice. This event provided medical students the opportunity to practice “real” medicine instead of just learning about it, bringing the clinical experience to their pre-clinical years. Figure 1. Case summary and initial physical exam, vital signs, labs Figure 2. rubric for simulation encounter Figure 3. Operator guidelines and transition points |